By Sevasti Evangelisti-Louta

The Beat Generation occupies a distinct and transitional period in American literature. Timothy S. Murphy (1998) describes William Burroughs by coining the term “amodernist” a writer critiquing both modernism and post-modernism, thus bridging the two movements. Similarly, Jeremy Standifird (2016) reads Burroughs as representing late modernism: a “period of rapid transition from one era to the next that still exudes some semblance of its most previous state” (4). This liminal identity is evident in William Burroughs’ earlier works composed while he was living in Mexico City.

His novella Queer—originally written in the 1950s as a sequel to his 1953 work Junkie but published in 1985—is a manifestation of opioid withdrawal. Laden with autobiographical allusions, it recounts the unrequited, drug-fueled romance between American expatriates William Lee and the distant Eugene Allerton. At the time, Burroughs was awaiting trial for what he claimed to be the accidental killing of his wife Joan Vollmer. In the appendix to the 2010 edition, he attributes his turn to writing on this traumatic event:

I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a life long struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out. (134)

In the story, his protagonist and alias, Lee, has self-exiled in Mexico City in order to avoid drug charges in the U.S. He wanders through Mexico’s gay scene, jumping from bar to motel in a cycle of indulgence. As the narrative unfolds, Lee becomes increasingly disillusioned, erratic and obsessive with his object of desire. He invites Allerton on a trip round South America in search of the hallucinogenic drug “yagé” (“the Final Fix,” in Burroughs’ words). This quest marks a turning point in the novel, where characters disintegrate and their identities destabilize. In this light, the several hotel scenes take on symbolic weight, functioning as ambivalent spaces expressing both longing and alienation. One such instance occurs in chapter 8:

They drove into Quito in a windy, cold twilight. The hotel looked a hundred years old. The room had a high ceiling with black beams and white plaster walls. They sat on the beds, shivering. Lee was a little junk sick. (71)

That night Lee dreamed he was in a penal colony. All around were high, bare mountains. He lived in a boardinghouse that was never warm. He went out for a walk. As he stepped off a street corner onto a dirty cobblestone street, the cold mountain wind hit him. He tightened the belt of his leather jacket and felt the chill of final despair.

Lee woke up and called to Allerton, “Are you awake, Gene?”

“Yes.”

“Cold?”

“Yes.”

“Can I come over with you?”

“Ahh, well all right.”

Lee got in bed with Allerton. He was shaking with cold and junk sickness.

“You’re twitching all over,” said Allerton. Lee pressed against him, convulsed by the adolescent lust of junk sickness.

“Christ almighty, your hands are cold.”

When Allerton was asleep, he rolled over and threw his knee across Lee’s body. Lee lay still so he wouldn’t wake up and move away. (74)

The hotel is a reflection of Lee’s state of mind. As he is dealing with drug withdrawal symptoms and plagued by feelings of exile, the hotel becomes a place where Lee rehearses his anxieties and at the same time a liminal space that accommodates and conceals the characters’ transgressive relationship. In homoerotic literature, the hotel—with its anonymity and sexual potential—is often conceived as a space where individuals become fully embodied outside the constraints of social (hetero)normativity. Burroughs, however, seems to challenge this tradition. His protagonist is denied the possibility for self-actualization and metamorphosis that the hotel would otherwise facilitate. In one of his various bizarre hallucinations Lee confesses that he is not “queer”, but rather “disembodied” (86).

As a setting, the hotel room also exudes a sense of stasis. Lee’s quest for yagé is nothing more than an excuse to keep his love interest close, an escapist fantasy they will ultimately be forced to abandon. Burroughs again comments on the novella’s ending in the appendix:

Dead end. And Puyo can serve as a model for the Place of Dead Roads: a dead, meaningless conglomerate of tin-roofed houses under a continual downpour of rain. Shell has pulled out, leaving prefabricated bungalows and rusting machinery behind. And Lee has reached the end of his line, an end implicit in the beginning. [Lee] is left with the impact of unbridgeable distances, the defeat and weariness of a long, painful journey made for nothing, wrong turnings, the track lost, a bus waiting in the rain . . . back to Ambato, Quito, Panama, Mexico City. (130)

Their search for the drug ultimately leads to an impasse. No satisfactory resolution is afforded to either character and they drift apart. Considering Burroughs’ own latent homosexuality, as well as his substance abuse and self-loathing, the ending of Queer reads as a kind of self-punishment, a way to deny his alter ego the intimacy he could not allow himself.

Despite the satirical narrative voice, Lee’s feelings of superiority, stemming from his North American, white, upper-class background, taint his perception of the native people of South America. In one of his hotel stays with Gene, he lashes out with blatant racism:

The inside wall to Lee’s room stopped about three feet from the ceiling to allow for ventilating the next room, which was an inside room with no windows. The occupant of the next room said something in Spanish to the effect Lee should be quiet.

“Ah, shut up,” said Lee, leaping to his feet. “I’ll nail a blanket over that slot! I’ll cut off your fucking air! You only breathe with my permission. You’re the occupant of an inside room, a room without windows. So remember your place and shut your poverty-stricken mouth!”

A stream of chingas and cabrones replied.

“Hombre,” Lee asked, “¿En dónde está su cultura?” (95)

In this excerpt, the hotel room is framed as a quasi-colonial space that reinforces the North American visitor’s sense of entitlement at the expense of the local population, whom Lee dehumanizes and threatens. The hotel room’s layout echoes class and racial discrimination; while the impoverished natives are confined to a room without a view, the privileged northerners treat them like expendable parasites. Lee’s claim over their access to oxygen is a repulsive reminder of the power dynamics lying beneath the narrative.

Interestingly, the epilogue “Two Years Later: Mexico City Return” complicates things further. The narrator shifts from third to first person, suggesting a collapse between narrator, character and author. This final chapter finds Lee returning to Mexico City hoping to find some kind of closure amidst his hallucinatory visions. South America is ultimately presented as a place for transgression and debauchery for the expat community, a utopia for the privileged, but at the same time a trap.

While Burroughs only recently found a place in the gay literary “canon”—long overshadowed by his reputation as an “addict writer” (Białkowska)—Queer continues to resonate. Luca Guadagnino’s 2024 film adaptation amplifies the novella’s symbolism and gay themes and has significantly renewed both scholarly and general interest in the original text. The film pushes the original plot to an even more surrealist realm, with the anachronistic new wave/grunge soundtrack[i] and artificial-looking set design serving, according to the director, as “a projection of the author’s total imagination rather than a ‘period drama’” (Palladino). Still, the image of the hotel lingers—a cold, temporary and dislocated space where Lee’s “phantom” desire is both performed and denied. This phantom desire is the crux of Queer. By the end, Lee—much like Burroughs[ii]—has become completely alienated and disconnected from his physical self. From a political perspective, the hotel setting underscores Burroughs’ self-deprecating critique on the post-WW2 American expatriate as an identity caught in-between indulgence and self-destruction.

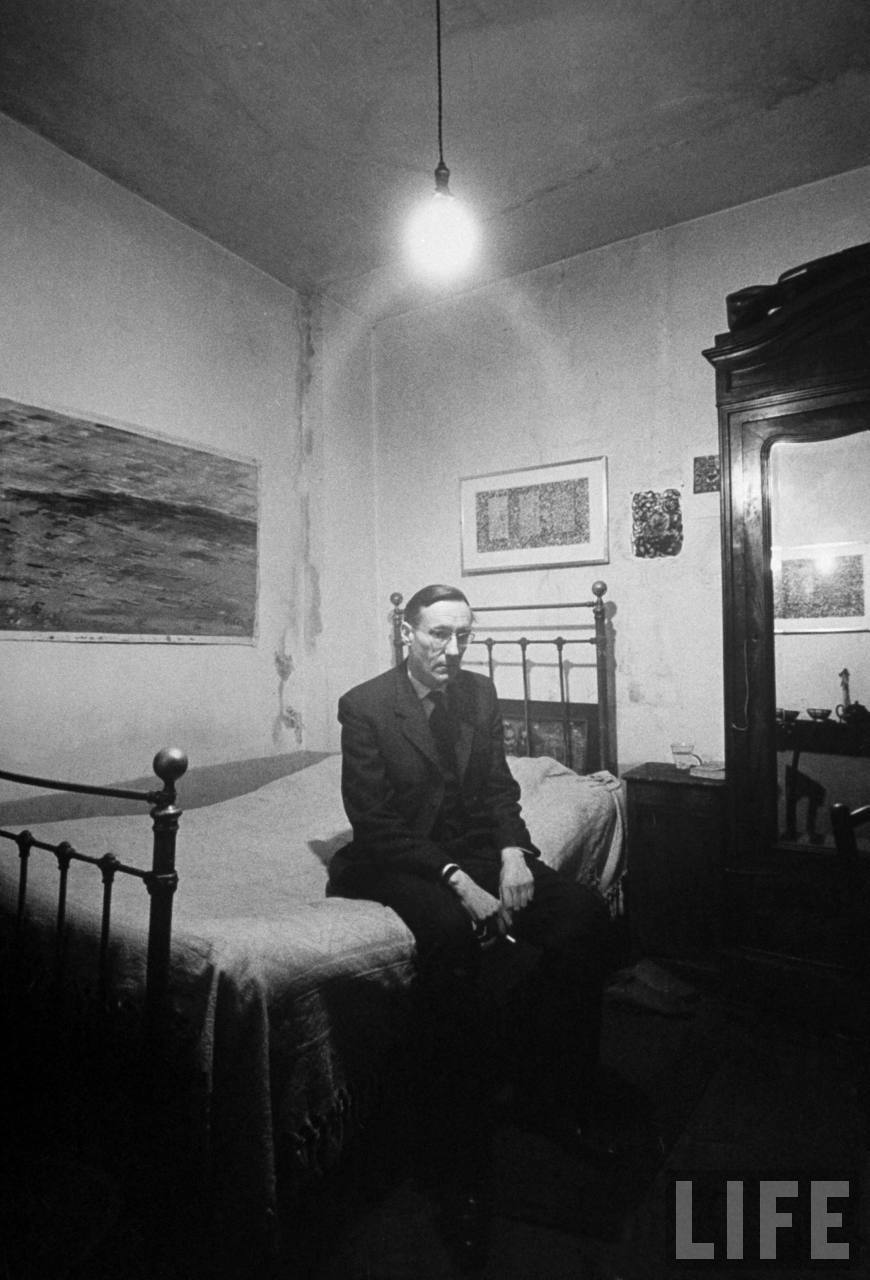

A palimpsestic space and image, the hotel interweaves the author’s literary identity and personal life. In 1954, Burroughs moved to Morocco and resided in the Villa Muniria in Tangier. His dubbing of the city as “the Interzone”[iii] explains his fascination with Tangier’s syncretic character. It was in this unrestrained environment that Burroughs wrote his acclaimed experimental novel Naked Lunch. Along with other Beat writers, Burroughs also dwelled in the Beat Hotel in Paris during the late 50’s, a run-down building whose idiosyncratic owner encouraged the tenants’ artistic expression.

William S. Burroughs’ works are illuminated when read through the nuanced experience of exile. Naturally, then, his narrative surrogate is haunted by a sense of “disembodiment”, a type of alienation manifested and magnified via the hotel. In Queer and other subsequent works, exile ultimately not only refers to geography, but also evokes an intricate mode of psychological, spatial and existential being.

Notes

[i] Burroughs did, after all, collaborate with Kurt Cobain on a spoken word piece set to music in 1992. (https://www.rocknrollburroughs.com/interzone/2018/4/5/nirvana-the-hard-way)

[ii] Interestingly, Burroughs earned the nickname “El Hombre Invisible” (The Invisible Man) during his time in Tangier (from the Introduction to Queer. Penguin, 2010 p. 3)

[iii] The “Interzone” was the International Zone of Tangier from 1923 to 1956, administered by several foreign powers. It functioned as a politically neutral, tax-free zone with loose regulations on trade, residency, and movement, naturally also attracting various 20th century intellectuals.

Works Cited

Białkowska, Anna. Lee and the Boys’ – A Queer Look at William S. Burroughs. New Perspectives in English and American Studies: Vol. 1: Literature. Jagiellonian University Press, 2022. pp. 298–306.

Burroughs, William S. Queer. Penguin: 2010.

Murphy, Timothy S. Wising Up the Marks: The Amodern William Burroughs. University of California Press, 1997. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0580030m/.

Palladino, Valentina. “Inside Luca Guadagnino’s Lush, Queer Sets at Cinecittà Studios in Rome.” The World of Interiors, 2024. https://www.worldofinteriors.com/story/luca-guadagnino-queer-sets-cinecitta-rome

Standifird, Jeremy. Bridging the Gap Between Modernism and Post-Modernism: Burroughs’s Junky and Naked Lunch Take Center Stage. Southern New Hampshire University, 2016.

Sevasti Evangelisti-Louta is a final-year undergraduate student of English Language and Literature at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. She is an aspiring literary scholar with a keen interest in twentieth-century comparative and feminist literature (mostly Modern Irish and Scottish Literature).

Cover Image: Burroughs on the bed of his hotel room. Location: Paris, France. Date taken: October 1959. Photographer: Loomis Dean. Source: LIFE Magazine, Hosted by Google.

A photograph depicting William S. Burroughs, with his face partly obscured in shadow, originally taken by Allen Ginsberg. Signed Photo Taken After “Queer” Manuscript Begun During Mexico City Murder Trial. Source: “University Archives,” https://www.universityarchives.com/auction-lot/allen-ginsberg-william-burroughs-signed-photo-t_D7340B1A14